One Brussels-based AISBL received over €4.15 million in EU funding between 2018 and 2023, surpassing €5 million in total after 2024. In 2022 alone, its executive director invoiced €21,352 monthly through his private company, absorbing more than 45% of the organisation’s total HR budget. While the website presented 11 team members, only 3 were officially employed; at least 4 others had been working full-time for 7+ years as so-called “freelancers”.

The organisation deliberately maintained fewer than 5 official employees to retain micro-AISBL status and avoid publishing full financial statements, as allowed under Article 3:47 of Belgium’s Companies and Associations Code. Its 2022 accounts declared €417,599 under “contract staff” and just €112,789 for employees — a 268% discrepancy never questioned by auditors or the board.

Audit reports signed off without issue, despite internal notes admitting violations of basic accounting rules such as the cut-off principle. Staff timesheets across 40+ EU projects reflected over 170 hours per month, per person, with no oversight. Over €800,000 in deferred EU project income remained parked on the books, lacking public explanation or scrutiny.

The context

Belgium’s institutions were formally informed of these practices starting in October 2023, with a full complaint and evidence file delivered by October 2024.

Despite the gravity of the allegations — including signs of fabricated timesheets, disguised employment, and the disproportionate use of public funds — the responsible authorities responded not with investigations, but with silence and deflection. No action. No follow-up.

We got vague replies, jurisdiction ping-pong, and a clear message: please stop asking questions. A full masterclass in evasion, confusion, and institutional amnesia.

Let’s be clear: this isn’t just negligence. It’s weaponized incompetence. Or worse — a tacit cover-up, protected by lifetime contracts and the comfort of jobs that don’t require consequences.

Public money is being drained, and the institutions designed to protect it are doing the exact opposite: nothing.

After months of bureaucratic back-and-forth, nearly every Belgian institution pointed in the same direction: SPF Finance — Belgium’s Federal Public Service for tax matters, the authority legally responsible for monitoring nonprofit financial compliance. It’s where complaints go in, and silence comes out.

Under Article 505 of the Belgian Criminal Code, especially following its February 2024 amendment, SPF Finance is explicitly empowered — and obligated — to investigate all forms of tax fraud, not just cases deemed “serious”. That means undeclared income, disguised employment, misuse of micro-AISBL status, or unexplained deferred project income all fall within their jurisdiction.

And yet: three separate letters were sent. With full documentation. With legal references. With clear, specific questions. The latest contacted were Filip Van de Velde, Chair of the Management Committee of the Belgian SPF Finance and SPF Finance press department.

The result? Zero response. No answers. No investigation.

This isn’t a matter of delay — it’s institutional refusal. Despite clear legal obligations and full authority to act, SPF Finance has so far demonstrated the same consistent behaviour as every other Belgian gatekeeper: defer, deflect, and disappear.

In a country where transparency is a legal requirement, SPF Finance appears to operate on a different rulebook: don’t ask, don’t reply, don’t investigate.

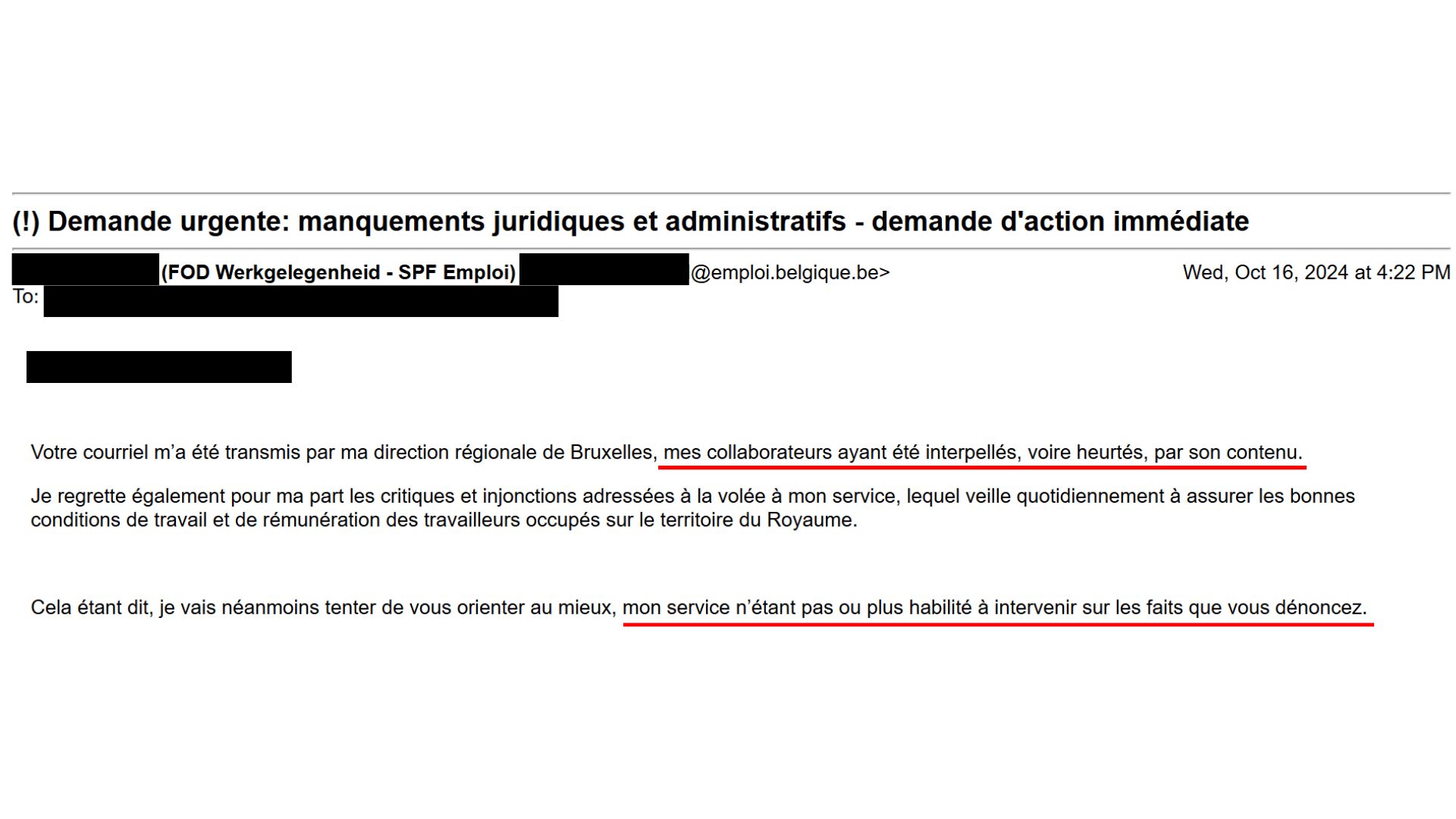

Belgium’s FPS Employment, Labour and Social Dialogue (French: SPF Emploi, Travail et Concertation sociale) is the authority tasked with enforcing labour law — including Article 328 of the Belgian Social Security Law, which explicitly prohibits false self-employment.

In theory, this means that when workers are contracted as “freelancers” but act like full-time staff — reporting to a manager, attending internal meetings, requesting leave, using company emails — the law requires action.

In practice? Not quite.

In October 2024, when presented with evidence of freelancers working full-time under employer control, SPF Emploi dismissed the case, effectively ensuring no investigation took place.

► The official response, signed by Ms. Cécile D., Inspector-General Advisor, on October 16, 2024, reads like satire: “my department is not or no longer authorized to intervene in the facts that you are reporting.”

Translation? We saw the red flags. But we’re not touching them.

To this day, SPF Emploi has not answered basic, legally relevant questions, such as: who ensures labour law compliance in EU-funded projects operating in Belgium? Are full-time “freelancers” with monthly invoices and fixed hours allowed under Belgian law? Are there limits to how long a private company (BVBA/SPRL) can invoice a single AISBL without becoming a de facto employee? Has any oversight been conducted on employment practices within heavily EU-funded AISBLs?

No answers. No investigation. No law enforcement.

The Belgian National Social Security Office (ONSS – French: Office National de Sécurité Sociale) is legally tasked with ensuring employers correctly declare work and remuneration, as required under Belgian labor regulations.

In October 2024, ONSS received clear, detailed evidence showing exactly that — misclassified workers who’d been invoicing monthly, full-time, for years, while performing core roles inside a well-funded Brussels-based AISBL.

Their first move? Close the file.

On November 7, 2024, the case was dismissed without action, and the inquiry redirected — where else? — to SPF Finance. (Dossier number SR3267824.)

► Two weeks later, on November 19, 2024, an administrative expert named David D. confirmed by email that “an investigation has been opened at this employer in order to regularize the situation”.

Fast forward to April 2025. The same freelancers are still there. The same invoices are still being issued monthly. The same executive director is still billing over €25,000 per month through his private company.

If there was an investigation, it seems to be stuck in a permanent lunch break. Because at ONSS the law is clear but enforcement is optional. Misclassification becomes the business model — and ONSS becomes its quiet enabler.

Banque Nationale de Belgique (National Bank of Belgium)

The National Bank of Belgium oversees financial reporting standards and compliance, including the obligation for AISBLs exceeding micro-entity thresholds to file detailed financial statements under Article 3:47 of the Belgian Code of Companies and Associations.

► Despite being notified in December 2024 about an AISBL reporting assets of €1,785,032 in 2021 and €1,816,709 in 2022 — well above the micro-AISBL limit of “1.562.000 euros pour le total des avoirs” — the Bank failed to flag discrepancies or trigger investigations.

This systemic neglect allows AISBLs to exploit transparency loopholes and avoid scrutiny, undermining the integrity of Belgian fiscal law.

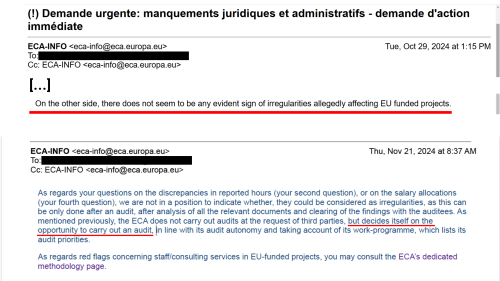

Mandated by Article 287 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), the ECA is tasked with ensuring EU funds are used legally, efficiently, and transparently. Despite its role as the EU’s financial watchdog, the ECA dismissed clear evidence of irregularities in an AISBL’s operations with vague references to audit methodologies, stating in October 2024: “There does not seem to be any evident sign of irregularities allegedly affecting EU-funded projects.”

By February 2025, the ECA reiterated its refusal to act, claiming: “We note that you addressed your letter to various other institutions, which might be in a better position to provide you feedback. Finally, we consider that we have already replied to your query in full and that your request is closed.“

This response disregards its legal obligation under Article 287 TFEU to examine external red flags and undermines public trust in its ability to safeguard EU finances. Directing inquiries to a methodology page instead of addressing concrete allegations demonstrates a systemic failure in accountability.

Case closed — not for lack of evidence, but for lack of interest.

European Commission & European Parliament

Under Article 325 TFEU, the Commission is responsible for protecting EU financial interests against fraud. It has been criticized for lacking comprehensive data on fraud levels and failing to establish effective systems to detect undetected fraud in EU-funded projects.

As the EU’s legislative body, the European Parliament oversees budgetary control and transparency in EU spending. Despite its power to demand accountability from member states and institutions, it has remained silent on systemic abuse within Belgian AISBLs receiving EU funds.

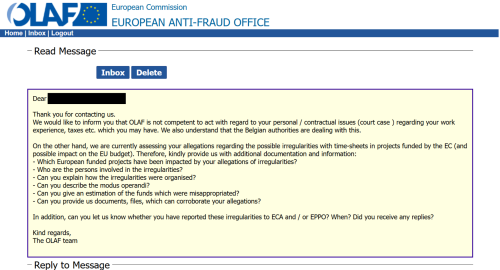

And back to OLAF (European Anti-Fraud Office)

The European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF) has a clear mandate. Despite receiving billions in EU funding, Belgium has seen only four (4) OLAF investigations in the last decade — a figure that raises eyebrows given the size of its EU-funded ecosystem.

In October 2024, OLAF received a formal complaint detailing systemic abuse within this Belgian AISBL, including fabricated timesheets and disguised employment arrangements. Instead of acting, OLAF requested the petitioner to compile the case for them — everything from modus operandi to supporting files.

By February 2025, after four months of “assessment”, OLAF was still deciding whether to open an investigation. By April 2025, six months later, still no answers.

OLAF’s reluctance to act raises serious concerns about selective enforcement and its unwillingness to address fraud allegations involving Belgian organizations.

The federal Ombudsman, tasked with investigating systemic violations under Belgium’s whistleblower law (November 28, 2022), initially dismissed a formal complaint regarding fraud in an AISBL on December 16, 2024.

The reasoning? The whistleblower’s allegations were deemed “private”, despite clear evidence of fiscal and social irregularities knowledge gained in a professional setting.

After receiving structured evidence akin to a courtroom submission, the ombudsman reversed its stance and deemed the complaint admissible.

But the story didn’t end there. Following a call with a forensic auditor in February 2025, the case was dismissed yet again. It took a legal masterpiece from the petitioner — brutally dismantling every argument made by the auditor — to force the ombudsman to act.

In March 2025, for the first time in this saga, meaningful action was taken: the ombudsman forwarded the evidence to Belgium’s Social Intelligence and Investigation Service (SIOD) for further investigation into false self-employment and social fraud. Not tax evasion. They do not do tax evasion as they consider it is OLAF’s job.

While their initial reluctance epitomized bureaucratic inertia, this unprecedented step marks a rare moment of accountability within Belgium’s institutional landscape.

For once, someone did their job.

Conclusion: lessons for a better Europe

This investigation reveals the cracks in a system designed to protect EU funds but often paralyzed by bureaucratic inertia and institutional deflection.

Yet, it also offers hope: the Belgian federal ombudsman’s eventual action proves that accountability is possible when institutions fulfill their responsibilities.

The EU is not broken — it is evolving. These revelations are an opportunity to strengthen oversight, demand transparency, and ensure public funds serve their intended purpose. By addressing these systemic flaws, we can build a Union that not only promotes progress but protects it.

A stronger Europe begins with accountability.