€ 21.352,87. € 38.976,12. Another EU-funded NGO executive director invoiced € 32.128 in October 2025. All three payments are real. All three are perfectly legal under current EU rules.

And almost nobody knows they exist.

This is the European Union’s HR blind spot — a structural flaw in the way EU-funded work is organised, reimbursed and overseen, which allows some NGO leaders to earn the equivalent of a commissioner-level income while remaining financially invisible to the public they claim to serve.

Across mainstream EU programmes, personnel costs represent between 60-80% of total expenditure, according to the European Commission’s own reporting. EU funding is, above all, funding for people. It pays for expertise, management, coordination and labour.

Yet when it comes to EU-funded NGOs, labour is the least transparent element of the system.

The reason is not a lack of rules. On paper, EU grant regulations are detailed and strict. Staff costs must be supported by employment contracts, payroll records, social-security contributions and time records. Contractors and service providers must be booked separately, under different cost categories.

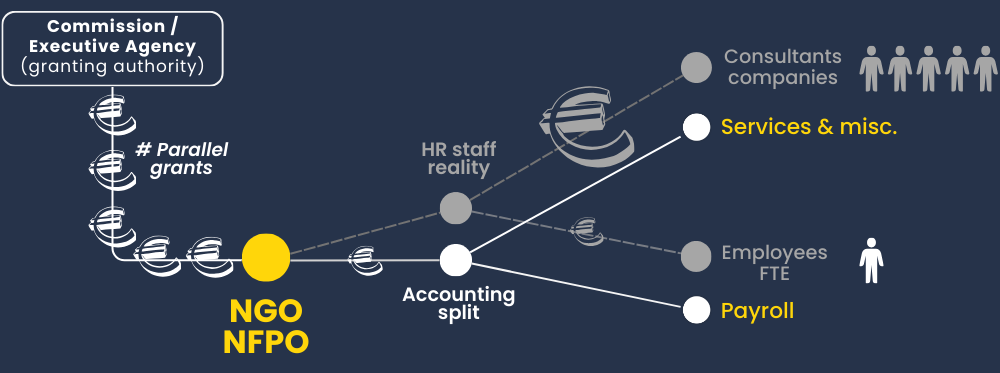

But this distinction — between “staff” and “services” — is precisely what creates the blind spot.

When an NGO leader is paid as an employee, their remuneration is, at least in theory, visible as payroll. When the same leader is paid through their own company, their income disappears into a generic accounting line labelled “services”. No pay range is disclosed. No comparison is possible. No public debate can take place.

From the outside, the person running a multi-million-euro EU-funded organisation can earn tens of thousands of euros per month while appearing, on paper, to have no salary at all.

This is not a marginal phenomenon. It is a recurring pattern.

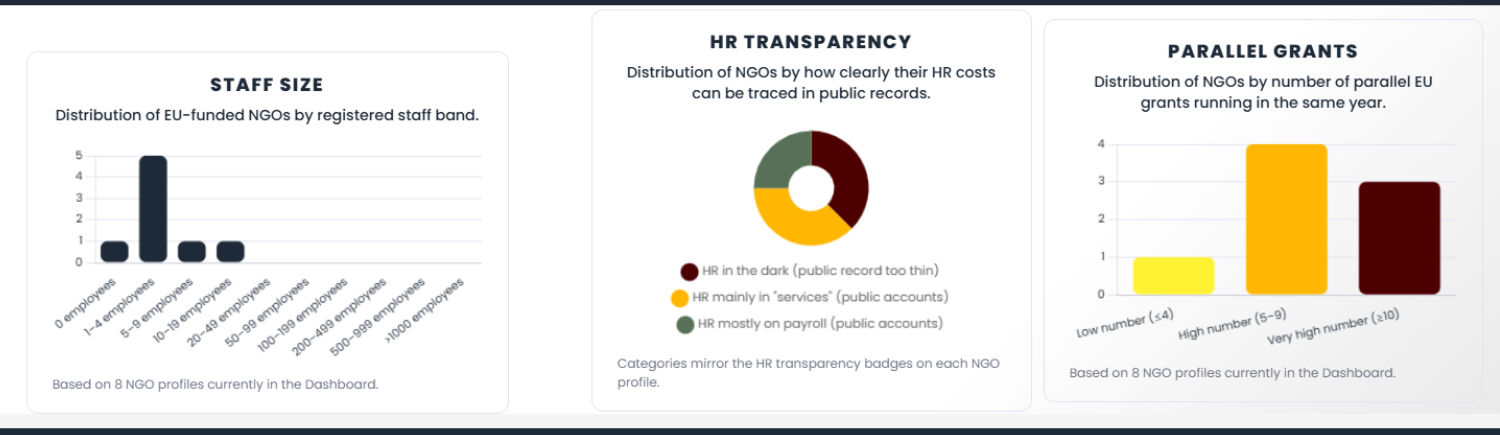

The same small staff runs parallel multi-million-euro EU grants. Only 1–4 people appear on payroll as full-time employees. Most of the work is billed, in the millions, as “services” and pushed into a vague “services & misc.” line, where the public does not see who was paid, for what, or the pay range.

In many cases, those services include long-term leadership functions, strategic management and operational control — the core work of the organisation.

Is this legal? Often, yes. Always, no.

EU funding rules do not ask whether it is appropriate for NGO leaders — who frequently advocate transparency, social justice and ethical governance — to earn private-sector-level incomes funded by public money, while remaining shielded from public scrutiny.

The problem does not stop at individual pay. It is systemic. Timesheets exist. Payroll records exist. Supporting documents exist. But they stay inside the NGO.

Not even EU agencies see who really worked on what. EU project officers manage grants one by one. Each project is assessed in isolation. Each has its own declared personnel costs, its own service contracts, its own reporting cycle. They do not reconstruct labour reality person by person, per all parallel grants. They do not see whether the same director totals as “100% project effort” across parallel grants while also running the organisation. They do not see whether millions booked as “services” correspond to real staff capacity. They reimburse based on HR totals per grant. No system totals how many hours one person declares across an organisation’s entire EU-funded portfolio.

Confidential discussions with European Commission project managers confirm this. Oversight is project-based, not people-based. Cross-project aggregation is not part of the system.

The consequence: even the EU itself cannot easily say who actually worked on what, for how long, and for how much, across EU-funded work.

This is not a failure of auditors. It is how the system is designed.

The European Court of Auditors has already warned that there is no reliable, consolidated overview of EU funding to NGOs and that information remains fragmented across systems. What that fragmentation produces, in practice, is a funding model that runs on trust — trust that declarations are accurate, trust that services reflect real work, trust that leadership remuneration aligns with public-interest values.

Trust without visibility is not accountability.

EU-level data

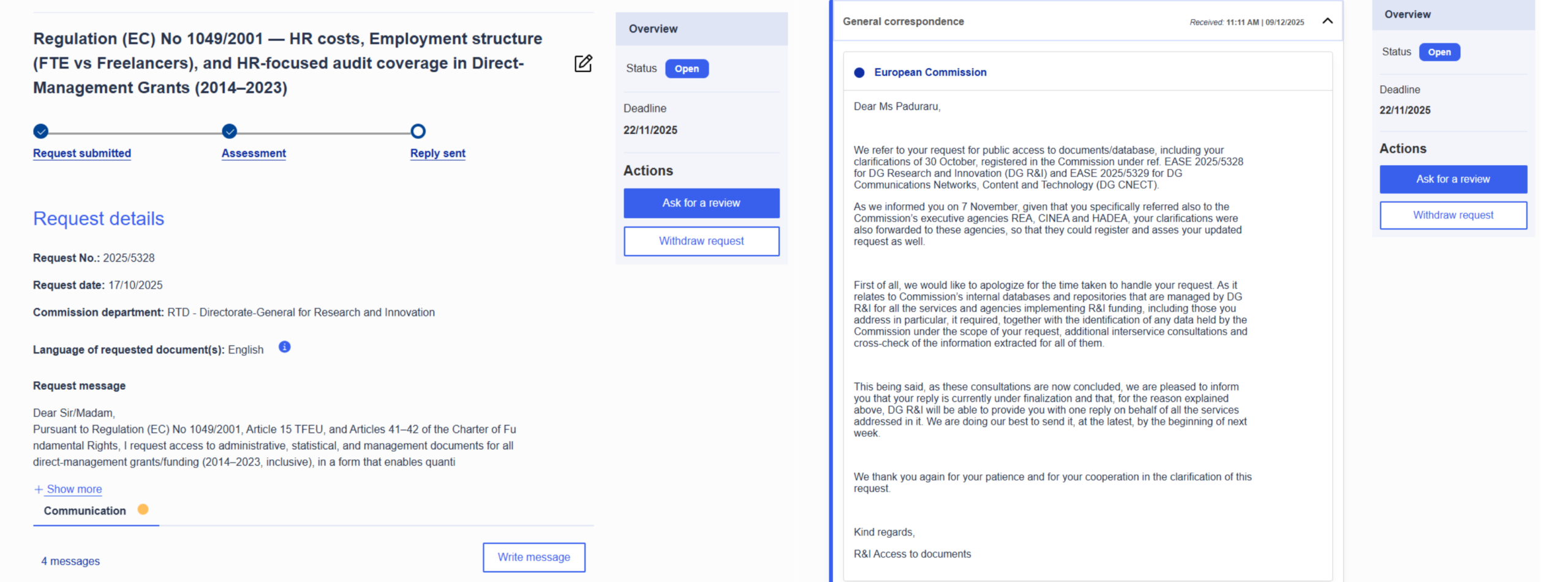

To test whether EU institutions themselves have a consolidated view of how labour is organised and remunerated in EU-funded NGOs, a series of freedom of information (FOIA) requests were submitted in October 2025 under Regulation 1049/2001.

The requests were deliberately narrow. They did not seek names, contracts, or operational case files. They did not target specific NGOs. They asked only for aggregated, non-personal administrative data that EU institutions routinely generate in the course of managing and overseeing EU grants.

One request, addressed to the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Research and Innovation and its executive agencies, asked for statistical information covering the past decade: how much EU funding had been reimbursed as personnel costs, how much as services or subcontracting, how often EU-funded NGO work relied on employees versus external contractors, and whether HR-related risks are systematically tracked in audits and controls. The request explicitly accepted partial access, anonymisation, and aggregated formats.

The Commission extended the legal deadline. By December, it confirmed in writing that the reply was under finalisation and that consultations between services were ongoing. By late January 2026 — close to three months after submission — no data had been released, no partial disclosure provided, and no explanation offered as to whether the requested aggregates exist or not.

A second request, addressed to the European Union’s anti-fraud office – OLAF, sought a different angle on the same issue. It asked whether OLAF holds non-casefile statistical information on investigations involving NGOs and non-profit entities, particularly those related to HR-irregularities such as misclassification of labour, inflated time records, or long-term service contracts resembling employment. It also asked whether OLAF’s databases classify investigations by type of irregularity or by entity category, in aggregate form.

OLAF’s reply was unequivocal — and revealing. OLAF confirmed in writing that it cannot provide — or does not hold — aggregated statistics on HR-related investigations involving NGOs, despite being the EU body mandated to protect the Union’s financial interests.

The pattern is striking.

On the funding side, the Commission cannot readily disclose aggregated HR data on how EU-funded NGOs organise labour and remuneration. On the oversight side, OLAF states that it does not hold aggregated information allowing it to identify HR-related risks involving NGOs as a category.

This does not mean that abuses occur. It means that the system is structurally incapable of seeing whether they do.

EU institutions reimburse HR costs as the largest component of NGO funding. They accept detailed time records, contracts and invoices at project level. But when asked to step back — to look across projects, across organisations, across years — the picture dissolves.

The delays and empty replies to these freedom of information requests do not point to secrecy. They point to something more fundamental: the absence of a consolidated, people-centred view of EU-funded labour.

In a system where NGO leaders can legally earn tens of thousands of euros per month through service contracts funded by public money, while appearing nowhere as salaried staff, the inability of EU institutions to produce even aggregated HR statistics is not a technical issue. It is the core of the problem.

Public money flows. Trust is assumed. Oversight exists — but only in fragments.

And when the institutions that design, fund and police the system cannot answer basic questions about who is paid, how, and at what scale, the HR blind spot is no longer an abstraction. It becomes a structural feature of EU governance itself.